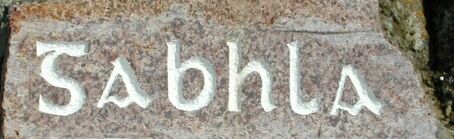

.... Now four miles to the northeast lay Gola, the largest of the Gweedore islands, and a tempting target if only the full gale would delay just a little longer. Two surf-fringed islets named Allagh, a curiously Islamic-sounding enclave in the Catholic west, guarded the approach to the slipway at Gola. I had looked forward to getting here for rest and shelter, however brief. But Gola, I now found, had an eerie, ghost-town atmosphere. Abandoned houses gazed like stunned animals out over the islands of Gweedore. Ashore, debris filled the ditches; fields and former gardens lay derelict, and the skeletons of rotting wooden fishing boats littered the pier and shingle shore. A scattering of solid, two-storey houses towered impotently above the Sound, looking from a low angle like the redundant monoliths of Easter Island. I was no stranger to abandoned houses, neglected land and the remains of long departed communities. The Irish coast, like the highlands and islands of Scotland, is littered with ruined crofthouses, ancient field patterns, abandoned piers and moorings, the recurring evidence of economic and social decay. And at one level Gola was just another abandoned island on the edge of one of Europe's most remote and economically backward regions. But what struck me most was the atmosphere of abandonment without decay. The houses could not yet be called ruins; one felt as though, like faithful dogs, they were just waiting for their owners to return. More than that, it was as if the island itself was still waiting. Whatever had happened here had happened relatively recently.

From the main track, which runs from the slipway to the north side of the island, countless shades of green made up the island palette. White specks of bog-cotton waved in the wind, lapwings wheeled and piped above the moorland, and the potent scent of the sea was on the Breeze. In the dazzling freshness of the landscape, and the beauty of its setting it was almost possible, for a short time, to overlook its ghosts, but all around stood poignant reminders of a recently vanished population. Discarded peatbanks still had spades sticking out proud, as though their owners had merely taken a short tea-break. I could still imagine the playground laughter as I passed the island school: a school which had a roll of sixty laughing children in 1930, and was still open in 1966, the year I had started school myself.

From close-up the houses, like giant severed heads with gaping mouths and pecked-out eyes, seemed to peer sightlessly out over the islands of Gweedore. Spacious, two-storey structures, sturdily built of local granite, they must have been fine, comfortable homes in their time. Everything useful or valuable had been stripped from them, but many still had sound roofs and dry interiors. What memories had they of peat-warmed rooms and busy families? Inside the highest house on the island I climbed a wooden staircase and looked out of a top floor window. Patiently in the distance the sea breathed and sighed, and the changing lights of its surface shone through the frameless window onto the pitch-pine panelling of the room. Despite that, the house remained heavy around me; the presence of the recent past filled the rooms like an odorless gas, and the day was full of questions. What had Gola been like as a living island? Where were its people, and why had they left? Would human communities ever return to these islands?

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries most of the Gweedore islands, were used for seasonal cattle grazing and a little fishing. But by the mid-nineteenth century fishing had begun to change from a supplementary activity to a dominant one. The population of the area, as in much of Ireland, was rising more rapidly than anywhere else in Europe, and the sea was one of the few resources able to supply local needs. And, as the economy of west Donegal shifted from a subsistence to a commercial basis, fishing assumed additional prominence as a source of cash income. The people of Gola became fishermen first and foremost, and the use of the land was relegated to second place.

Throughout the world the history of fishing has been dominated by the increasing centralization, mechanization, and indeed industrialization, of fishing activities, with bigger boats based at larger ports able to travel and fish ever further afield. Donegal was no exception. Outlying islands and small ports, with their small-scale, low capital fishing fleets, became unable to compete with the sophistication of the equipment and the scale of operations at the big ports. By the early part of this century fishermen in areas such as the Aran and Blasket islands and west Donegal began to feel the effects of competition with larger and better equipped boats from Scotland and England - especially the fleets of powerful steam drifters. Gola was unusual in that, despite these problems, despite growing transport costs and the Troubles, for a short time at least, fishing actually grew in importance. The main pier, built at the end of the nineteenth century by the Congested Districts Board, is large and well sited. Protected by an outcrop of rock from the north and northeast, and by the curve of the island from the west, it freed fishermen from dependence on any particular tide. Gola fishermen were able to continue to work throughout the year, and the island even became a summer base for fishermen from the mainland.

It seems that it was the growing pattern of seasonal labour migration, rather than the direct effects of the mechanization of fishing which eventually led to the decline and ultimate fall of Gola. Seasonal human migration from the glens, coasts and islands of the Rosses and Gweedore to Scotland and England for paid work, increased in importance during the nineteenth century. Being the only source, other than fishing, of bringing hard cash into local families, it quickly became the outstanding feature of this area's economic and social life. In some areas almost all the able-bodied men, girls and even children would leave their homes for six months of the year in order to find seasonal farm, construction or domestic work, mainly in rural Scotland. Increasingly in the twentieth century the migrant workers were drawn to the cities where building sites and factories offered more year-round employment, and they became permanent emigrants. The social impact of the cities on the migrant workers, who returned home to the glens and the islands, soon began to show in their lives. Because of the seasonal opportunities offered by the fishing, Gola was affected relatively late by the inevitable crisis of changing values, but the onset of population decline, though belated, was rapid and dramatic.

When the first few families leave an island community, the reallocation of available resources, such as land or peatbanks, may initially mean a partial rise in living standards for those who stay behind. However, this is usually not adequate to compensate for the deterioration of local social conditions, or to compete with the imagined standards of living available elsewhere. As the population dwindles, certain communal activities such as track repairs, ditch maintenance or peat gathering become more difficult; services - such as buses, shops, schools, pubs and ferries - eventually become uneconomic to run, and each family increasingly has to provide for its own needs. When the last family with children leaves an already ailing island, that island ceases to be a self-perpetuating community; Almost every aspect of island life is from that moment caught in an accelerating fatal spiral. It took less than a century for Gola once a thriving community of two hundred people to become an island of ghosts.

All the clearer for being an island, more poignant for being so recent, Gola is as powerful an illustration as you could hope to find, of what had happened along much of Ireland's Atlantic edge. Somewhere in its desolate salt-fringed loneliness there is an important lesson in human transience; a reminder of the fragile impermanence of men, families, even whole human communities in the face of the great or gradual tide-like sweeps which we call economics.

Halfway along the Gola pier a little shrine and effigy of 'Our Lady' had been carefully built into the rock where fishermen would once have stood and prayed before and after trips to sea. The fishermen were now gone, but 'Our Lady' was still there and I wished I could have asked her: to what extent was it sheer necessity and survival, and to what extent was it the seductive images of mainland and city life, that drove the people from Gola? And did they really find the grass greener, or were those images eventually to prove as far removed from reality as the ones many of us now hold of island life? The last thing I wanted was to get storm-bound among the ghosts of Gola; and from high on the Gola wasteland I could see that a further, relatively sheltered, area of sea existed beyond: that another couple of miles might yet be snatched before the impending gale. So I relaunched the kayak, skirted Gola and headed northeast past the last two islands of the Gweedore archipelago......

.... Now four miles to the northeast lay Gola, the largest of the Gweedore islands, and a tempting target if only the full gale would delay just a little longer. Two surf-fringed islets named Allagh, a curiously Islamic-sounding enclave in the Catholic west, guarded the approach to the slipway at Gola. I had looked forward to getting here for rest and shelter, however brief. But Gola, I now found, had an eerie, ghost-town atmosphere. Abandoned houses gazed like stunned animals out over the islands of Gweedore. Ashore, debris filled the ditches; fields and former gardens lay derelict, and the skeletons of rotting wooden fishing boats littered the pier and shingle shore. A scattering of solid, two-storey houses towered impotently above the Sound, looking from a low angle like the redundant monoliths of Easter Island. I was no stranger to abandoned houses, neglected land and the remains of long departed communities. The Irish coast, like the highlands and islands of Scotland, is littered with ruined crofthouses, ancient field patterns, abandoned piers and moorings, the recurring evidence of economic and social decay. And at one level Gola was just another abandoned island on the edge of one of Europe's most remote and economically backward regions. But what struck me most was the atmosphere of abandonment without decay. The houses could not yet be called ruins; one felt as though, like faithful dogs, they were just waiting for their owners to return. More than that, it was as if the island itself was still waiting. Whatever had happened here had happened relatively recently.

From the main track, which runs from the slipway to the north side of the island, countless shades of green made up the island palette. White specks of bog-cotton waved in the wind, lapwings wheeled and piped above the moorland, and the potent scent of the sea was on the Breeze. In the dazzling freshness of the landscape, and the beauty of its setting it was almost possible, for a short time, to overlook its ghosts, but all around stood poignant reminders of a recently vanished population. Discarded peatbanks still had spades sticking out proud, as though their owners had merely taken a short tea-break. I could still imagine the playground laughter as I passed the island school: a school which had a roll of sixty laughing children in 1930, and was still open in 1966, the year I had started school myself.

From close-up the houses, like giant severed heads with gaping mouths and pecked-out eyes, seemed to peer sightlessly out over the islands of Gweedore. Spacious, two-storey structures, sturdily built of local granite, they must have been fine, comfortable homes in their time. Everything useful or valuable had been stripped from them, but many still had sound roofs and dry interiors. What memories had they of peat-warmed rooms and busy families? Inside the highest house on the island I climbed a wooden staircase and looked out of a top floor window. Patiently in the distance the sea breathed and sighed, and the changing lights of its surface shone through the frameless window onto the pitch-pine panelling of the room. Despite that, the house remained heavy around me; the presence of the recent past filled the rooms like an odorless gas, and the day was full of questions. What had Gola been like as a living island? Where were its people, and why had they left? Would human communities ever return to these islands?

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries most of the Gweedore islands, were used for seasonal cattle grazing and a little fishing. But by the mid-nineteenth century fishing had begun to change from a supplementary activity to a dominant one. The population of the area, as in much of Ireland, was rising more rapidly than anywhere else in Europe, and the sea was one of the few resources able to supply local needs. And, as the economy of west Donegal shifted from a subsistence to a commercial basis, fishing assumed additional prominence as a source of cash income. The people of Gola became fishermen first and foremost, and the use of the land was relegated to second place.

Throughout the world the history of fishing has been dominated by the increasing centralization, mechanization, and indeed industrialization, of fishing activities, with bigger boats based at larger ports able to travel and fish ever further afield. Donegal was no exception. Outlying islands and small ports, with their small-scale, low capital fishing fleets, became unable to compete with the sophistication of the equipment and the scale of operations at the big ports. By the early part of this century fishermen in areas such as the Aran and Blasket islands and west Donegal began to feel the effects of competition with larger and better equipped boats from Scotland and England - especially the fleets of powerful steam drifters. Gola was unusual in that, despite these problems, despite growing transport costs and the Troubles, for a short time at least, fishing actually grew in importance. The main pier, built at the end of the nineteenth century by the Congested Districts Board, is large and well sited. Protected by an outcrop of rock from the north and northeast, and by the curve of the island from the west, it freed fishermen from dependence on any particular tide. Gola fishermen were able to continue to work throughout the year, and the island even became a summer base for fishermen from the mainland.

It seems that it was the growing pattern of seasonal labour migration, rather than the direct effects of the mechanization of fishing which eventually led to the decline and ultimate fall of Gola. Seasonal human migration from the glens, coasts and islands of the Rosses and Gweedore to Scotland and England for paid work, increased in importance during the nineteenth century. Being the only source, other than fishing, of bringing hard cash into local families, it quickly became the outstanding feature of this area's economic and social life. In some areas almost all the able-bodied men, girls and even children would leave their homes for six months of the year in order to find seasonal farm, construction or domestic work, mainly in rural Scotland. Increasingly in the twentieth century the migrant workers were drawn to the cities where building sites and factories offered more year-round employment, and they became permanent emigrants. The social impact of the cities on the migrant workers, who returned home to the glens and the islands, soon began to show in their lives. Because of the seasonal opportunities offered by the fishing, Gola was affected relatively late by the inevitable crisis of changing values, but the onset of population decline, though belated, was rapid and dramatic.

When the first few families leave an island community, the reallocation of available resources, such as land or peatbanks, may initially mean a partial rise in living standards for those who stay behind. However, this is usually not adequate to compensate for the deterioration of local social conditions, or to compete with the imagined standards of living available elsewhere. As the population dwindles, certain communal activities such as track repairs, ditch maintenance or peat gathering become more difficult; services - such as buses, shops, schools, pubs and ferries - eventually become uneconomic to run, and each family increasingly has to provide for its own needs. When the last family with children leaves an already ailing island, that island ceases to be a self-perpetuating community; Almost every aspect of island life is from that moment caught in an accelerating fatal spiral. It took less than a century for Gola once a thriving community of two hundred people to become an island of ghosts.

All the clearer for being an island, more poignant for being so recent, Gola is as powerful an illustration as you could hope to find, of what had happened along much of Ireland's Atlantic edge. Somewhere in its desolate salt-fringed loneliness there is an important lesson in human transience; a reminder of the fragile impermanence of men, families, even whole human communities in the face of the great or gradual tide-like sweeps which we call economics.

Halfway along the Gola pier a little shrine and effigy of 'Our Lady' had been carefully built into the rock where fishermen would once have stood and prayed before and after trips to sea. The fishermen were now gone, but 'Our Lady' was still there and I wished I could have asked her: to what extent was it sheer necessity and survival, and to what extent was it the seductive images of mainland and city life, that drove the people from Gola? And did they really find the grass greener, or were those images eventually to prove as far removed from reality as the ones many of us now hold of island life? The last thing I wanted was to get storm-bound among the ghosts of Gola; and from high on the Gola wasteland I could see that a further, relatively sheltered, area of sea existed beyond: that another couple of miles might yet be snatched before the impending gale. So I relaunched the kayak, skirted Gola and headed northeast past the last two islands of the Gweedore archipelago......