Nobody knows exactly when monks first settled on Skellig Michael but the style of building suggests the 6th century onwards. There are other examples of this style and this date at many points of lreland's west coast - but none in such

perfect repair as the Skellig Michael monastery. In A.D. 795, the first Viking attacks from Scandinavia were launched on the Irish coast, and the Skellig settlement did not escape for long. The early Irish manuscripts, the Annals of lnnisfallen, Annals cf Ulster and Annals of tbe Four Masters, contain only scant information on these raids. In A.D. 812, the Skellig monastery was sacked. Again in 825, as reported in the Annals of Ulster and Annals of lnnisfallen, the Vikings came and this time they took Etgal, Abbot of Skellig, and starved him to death. Legend tells that in 993 Viking Olav Trygvasson, who was later to become King of Norway and whose son Olav II, was to become patron

saint of Norway, was baptised by a Skellig hermit.

Des Lavelle in "The Skellig Story"

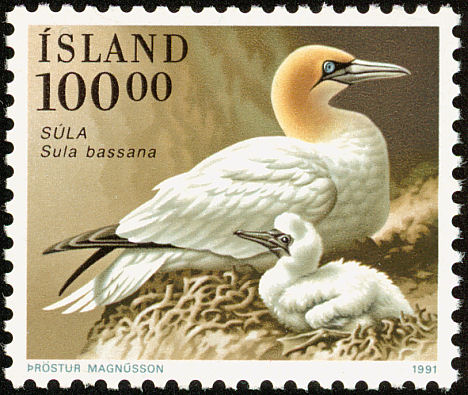

The gannet is Ireland's largest seabird, with a wingspan of two metres. Their breeding colonies are limited to eastern Canada, Iceland and North West Europe, and most are located on small islands and inaccessible cliffs. In Ireland there

are four main colonies, the largest, with nearly 30,000 pairs, being on Sceilg Bheag. Gannets catch fish by plunging into the shoals from a great height.

Oscar J. Merne (National Parks and Wildlife Service in the

An Post booklet on Birds of Ireland stamps.

| Gannet Colony | Number |

| Skellig | 26,436 pairs |

| Saltees | 2,050 pairs |

| Dursey - Bull Rock | 1,815 pairs |

| Ireland's Eye | 202 pairs |

| Clare Island | 3 pairs |

| Lambay | ? * |

| * Gannets first began breeding on Lambay in 2007 | |

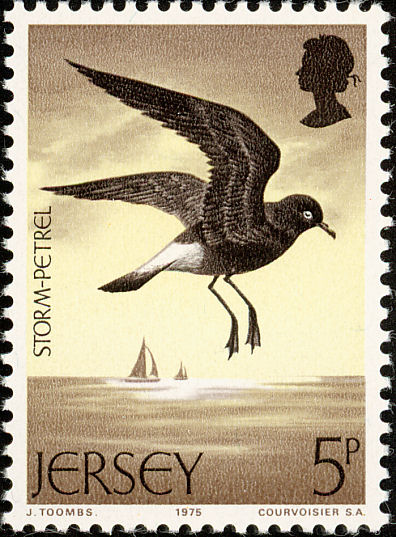

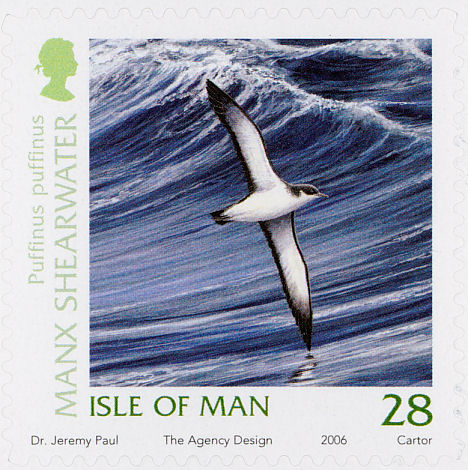

| Bird | Number | |

| Gannet | 26,436 pairs | |

| Storm Petrel - More | 5,000 pairs | |

| Manx Shearwater | 2,370 pairs | |

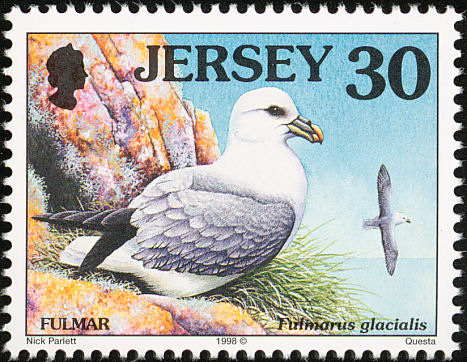

| Fulmar | 806 pairs | |

| Puffin - More | 4,000 individuals | |

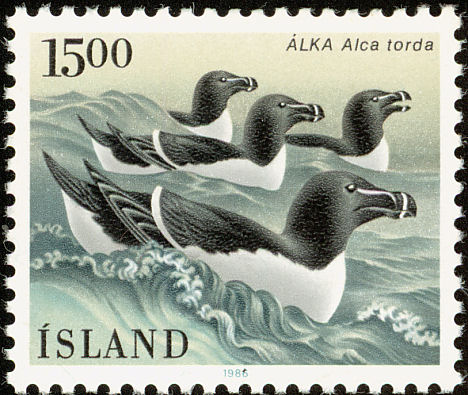

| Razorbill | c.4,000 individuals | |

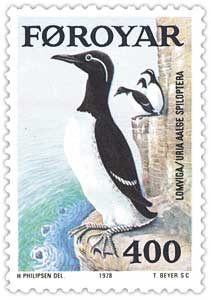

| Guillemot | 2,551 individuals | |

| Kittiwake | 944 pairs | |

| Chough | 1 pair | |

| Figures per NPWS website. These numbers indicate the presence of and population size of breeding birds. | ||

| Brian Wilson described a visit to the Skelligs in his book,

Dances with Waves about his journey by kayak around the entire coast of Ireland. (Published by The O'Brien Press) |

It was not until I was within a mile of its cliffs that Little Skellig at last stood out as a distinct mass from Skellig Michael. Towering above the white-capped waves, a bright guano-limewash highlighted the saw-ridged form of the high-rise sea bird colony. At first sight what looked like a plume of volcanic smoke hung over the island's four hundred foot peak; but greater proximity brought better definition: thousands of gannets were swarming in a flight-cloud so dense as to reduce the daylight. The skyway filled to saturation with white, whirring adult birds. The whole island too was alive with creamy-headed gannets; every available ledge on the serrated cliffs and pinnacles had been claimed.

Gannets, sometimes called solan geese, are large birds by any standard - the size of flying tom-cats, with five-foot wingspans - consuming considerable quantities of fish, and producing proportionately copious amounts of excrement. And Little Skellig, one of the largest gannetries in the world, is home to no fewer than twenty-three thousand pairs! As I paddled directly below the wheeling, thickening gannet cloud a simple biological equation became clear: most of what goes in must come out; and all of what comes out must come down. All around me guano-bombs began to splatter the sea's surface. Several near misses were followed by a large green Splat! which covered thirty square miles of Kerry on my deck map. Then, time and time again, in rapid succession, I was being bit: on the kayak, on my jacket, my hands and - most disconcertingly - right on the head! It was like being the unarmed quarry in a paintball wargame as I battled onward, unable to retaliate, running a gauntlet of guano. The foul-smelling liquid skittered over my forehead, ears, neck, and soon spread in fishy runnels to the few places which hadn't already been direcly hit. Fearful of the potentially disastrous effect of a direct hit in the face, I was keeping my eyes shielded and low and thanking Mother Nature that noses are designed with the nostrils facing downward, but my hair and head received a thorough covering. When a warm green gob dropped down my neck, l shivered in disgust, and finally abandoned the detached ornithological term 'guano'. Under full siege the only appropriate term is shit! shit! SHIT! and my paddle strokes increased to full panic level to escape from the lee of Little Skellig as soon as possible.

l emerged from the gannet cloud thoroughly caked in a rapidly hardening whitewash, looking, I supposed, like a scale replica of the island itself, and unable, for the moment to do anything about it. Beyond the slight shelter of Little Skellig, the sea took on an extra dimension. A large swell had built up and was breaking heavily in places, sometimes from a height of five feet - well above eye level when you're sitting in a kayak and quite daunting when eight miles from land. The sudden need to perform decisive bracing strokes - sweeping the paddle across the water's surface to gain the extra support necessary to right the kayak using a hip movement - gave the situation an extra edge of tension. Skellig Michael now lay across a final mile of heavy water, its dramatic shape and massive berg-like presence tempting me ever onward. But the bright, bouncy morning was gone; cloud had closed in and the wind had increased to force five, and I began to doubt whether it would be possible to land on the rock.

Beneath the towering rocks of Skellig Michael I surged and stalled, rising and falling on reflected waves. A twelve foot swell was pounding against the landing platform, fully exposed to the sea's assault. One moment I was level with the waves worrying the concrete step; the next I would be plunging downward until the platform was several yards above my head. To have tried to land there would have risked serious damage to the boat - and probably also to me. Skirting the rock gingerly, I found a second landing site, away from the sea's main force, at a place named Blind Man's Cove, where a flight of steps from the lighthouse ended in a submerged concrete block. But even here the swell was flushing in with great force, before sucking suddenly back to reveal a great void above the ubiquitous tearing rock. Alone there was no way to land without damage to the kayak; and as the kayak was my only ticket back to St Finan's Bay, I couldn't take that risk.With a sinking heart I began to realise not only that I'd be unable to explore the Skellig, but that, after almost three hours in the kayak, I wouldn't even be able to stretch my legs and have a pee. The long low line of the mainland, from Dursey Head to the Blasket islands, was just a distant smudge on the eastern horizon.

Well, the wind strengthened and the sea grew yet bolder, and the long journey landward became one of my roughest and most protracted ever..........

|

Des Lavelle

describes an incident when gannet hunters from Dunquin fought with guards set by the owner in

The Skellig Story (Published by The O'Brien Press) |

The gannet is obviously in a very strong position today, and one can only suggest that the fluctuations in the colony's early history were due to 'harvesting'. About 150 years ago, gannets were fetching 1s.8d. to 2s.6d. (7p -12.5p) each, and as late as 1869 the Small Skellig was rented annually for the taking of feathers and young gannets. Indeed, high up on the south face of Small Skellig, hidden from passing boats, are the ruins of a man-made rectangular building which may have been a gannet-hunter's shelter. . . At breeding time the rock was guarded by a boat-crew of twelve men, 'well paid by the man who owned it', but this deterrent was inadequate, and Dunleavy - in Thomas O'Crohan's Tbe Islandman - tells an exciting tale of one unauthorized gannet-raid which ended in bloodshed.

This time a boat set out from Dunquin at night with eight men in her, my father among them, and they never rested till they got to the rock at daybreak. They sprang up it and fell to gathering the birds into the boat at full speed. And it was easy to collect a load of them for every single one of these young birds was as heavy as a fat goose. As they were turning the point of the rock to strike out into the bay, what should they see coming to meet them but the guard boat. They hadn't seen one another till that moment.

Then the activity began. The guards tried to take the Dunquin boatmen prisoners, but '. . . some of them sprang on board and they fell to hitting at one another with oars and hatchets, and any weapon they could find in the boat till they bled one another like a slaughtered ox.'

Although outnumbered by twelve to eight the Dunquin men won the fight and eventually got back to their own harbour with their boatload of gannets intact. When the vanquished guard boat reached its base) two men were dead, and the other ten were sent into hospital. 'After that they were less keen on that sort of chase and the guard was taken off the rock . . .'